Is 'Man the Hunter' Dead?

How do hunter-gatherers live? Do they divide jobs between men and women? Or is this a modern myth? I've talked with scholars from both sides of the debate. Here is my attempt to make sense of it.

A chapter is slowly closing. This is the longest chapter in the human story: the chapter of existing hunter-gatherers. Whether in the Kalahari or in the Amazon, modernity is likely to push this original economy out of existence. But as the ancient life-way fades away, curiosity about it is only increasing.

I have felt this curiosity for years. I have interviewed scholars on many difficult questions: Do hunter-gatherers wage war? Do they have happy families? Do they really work less for more?

Amidst many thorny questions, one thing was clear: Hunter-gatherers divide jobs between the sexes. Men hunt. Women gather. Nicknamed “Man the Hunter”, this theory was something stable that we could take for granted.

Then came 2023.

Several new articles brought attention to the role of women’s hunting. They earned huge media attention with Science itself declaring that new studies “kill the myth of ‘Man the Hunter’”. Newspapers followed suit, reporting confidently that “women have always hunted as much as men”. It looked like “Man the Hunter” was meeting his end even faster than the real hunting parties of the Kalahari.

So how did we get things so wrong for so long?

Perhaps we didn’t.

This is the conclusion I reached last fall. I had just interviewed one of the scholars at the eye of the storm: Cara Ocobock. Together with Sarah Lacy, she had just co-authored a piece titled “Woman the Hunter” filling the cover of the Scientific American.

Photo: Cover of the November 2023 issue of Scientific American

I learned a lot from the article. And I enjoyed our conversation. But in a manner so characteristic of my temperament, I concluded that there really was no fierce debate in the field. All scholars agreed on surprisingly many things.1

I was wrong.

I received several messages from various scholars explaining the gravity of the matter. Papers started coming out disagreeing with various claims made by proponents of “Women the Hunter”, whether on physiology or ethnography. My Twitter feed became a nasty place. I had clearly been wrong. The debate was very real.

For the past few months, I’ve tried to figure out where exactly the debate lies and what exactly should I believe. I am grateful to all the scholars who gave their time to consult with me on the matter – especially Sarah Lacy who did so on her maternity leave. Finally, I want to thank Katie Starkweather for coming to speak about the sensitive topic on the show. You can listen to our episode on Spotify, Apple Podcast, or wherever you get your shows. Or you can continue reading.

So what have I learned?

1. Women hunt. They do so in many groups today. But in how many groups? Not as many as some suggested.

Women can be excellent hunters. The Agta in the Philippines are a classic example. And the Agta are not alone. As Starkweather told me, women contribute greatly to net-hunting in groups like Aka of the central African rainforests. This fact has long been absent from popular literature. This is a pity. I fully agree with Starkweather’s claim that:

“The real value of the recent pieces is that it has brought women’s hunting back to the conversation.”

But this is not something that serious scholarship has been denying — not to my knowledge. The real pushback comes from unhelpful voices online.2

The scholarly controversy lies in the numbers. This was addressed by Cara Wall-Scheffler’s lab in an article that launched much of the current storm. Their conclusion? Women hunt in most modern-day groups — 79 % of those we have data on.

But this number is probably false. If you are interested in debunking the number, you can head to this article. Katie Starkweather was a co-author, as was my previous guest Vivek Venkataraman.

I won’t go through all the possible errors here. There are many. Some of them are technical. Others give pause even to my untrained eye. For example, the sample was clearly not done in the way the paper explained. As a more glaring mistake, the !Kung and Ju/'hoansi were coded as two separate groups. (As any anthropologist will tell you, this is like coding UK and Great Britain as two countries.) In sum, the real number is likely to fall below 79%, perhaps way below it.

More research on this is required. But we should also notice that this number does not tell us how often women hunted.

To make this point, Starkweather and I discussed the example of men and childcare: yes, men contribute to childcare in most communities. And yes, there are heroic dads. As Sarah B. Hrdy told me, there are probably more heroic dads today than ever before. But we should not deny that in most societies, childcare exhibits a strong division of labor.

Starkweather also noted something interesting about this example:

“There's a ton of variation in how much care dads are giving and what kind of care they're giving and all that kind of stuff. And it's a really interesting question!”

Interestingly, there is a fresh article applying this logic to the question of women hunting. Instead of asking “do women hunt”, the researchers have asked when and why do women hunt. For example, women seem to hunt more when it’s done close to the camp and when hunts are assisted by dogs. But returning to Starkweather, she continued:

“[Dads helping sometimes] doesn't mean that there's no division of childcare labor, because there clearly is. And so the question then about women's hunting is how frequently does it happen?“

2. Men hunt more.

According to one popular reaction, only patriarchal bias could produce a theory such as “Man the Hunter”. Indeed, I’ve seen many online comments claiming that it just doesn’t make sense that half of the group would be left out of the hunt.

This is clearly false. Women are often “left out” of the hunt just as men are “left out” of gathering. This is a robust pattern across the ethnographic record. Unfortunately, this can be mis-used to suggest that women never hunt, or worse, that women cannot hunt. The efforts of Wall-Scheffler, Ocobock, and Lacy have thankfully pushed these views into the dustbin where they belong. But the general pattern remains unchallenged.

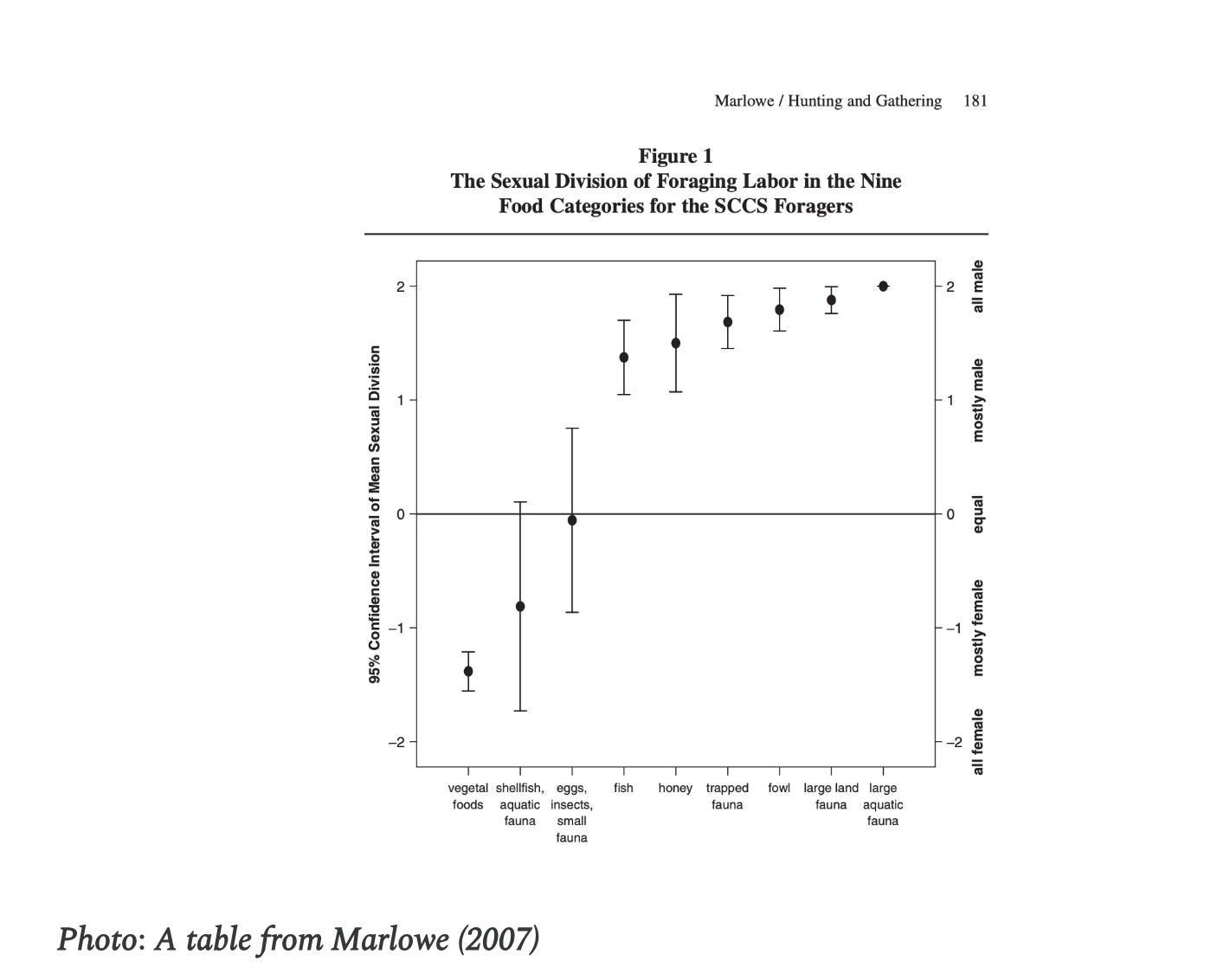

Below is the relevant data from Frank Marlowe.

Marlowe’s data shows a remarkably strong sexual division of labor. I would guess that this is even stronger than in childcare.

Naturally, his numbers might be wrong. The ethnographers might have been biased. Marlowe’s analysis might be unreliable. But no one has stood up to speak against them – not that I know of. Ocobock explicitly told me that she “might disagree with Marlowe here and there” but was not challenging the main point. When I asked Starkweather if any serious scholar has suggested numbers close to 50:50, she responded with a firm “no”.

This supports my original conclusion: men do most of the hunting. We shouldn’t slip from more to all. But neither should we deny the more—not if we want accurate models of the forager lifestyle. As Starkweather, Venkataraman and colleagues put it in their paper:

“In correcting the misapprehension that women do not hunt, we should not replace one myth with another.”

Importantly, Starkweather warned me against taking this as evidence of patriarchy. I will return to this point in point 4. But first, we need to address the elephant in the room: all the data so far is about modern-day hunter-gatherers. What about the deep past?

3. We don’t know how often women hunted in the past. And this is where things get tricky.

In our private conversation, Sarah Lacy told me she is mostly interested in evidence from the deeper past. She is a paleoanthropologist. In plain English, she studies stones and bones. And she is deeply critical of substituting stones and bones for evidence on modern-day hunter-gatherers — of using modern humans as “living fossils”.

Starkweather and Venkataraman take a different position. For them, studying hunter-gatherers is not the study of “living fossils” — it is the study of strategies that allow humans to thrive in the wild. If most hunter-gatherers divide jobs between men and women, it is probably because sharing jobs makes sense for them. And so, humans probably did so in the past, too. Or so goes the theory.

This is a tricky debate in itself. But it gets even trickier when we move to the stones and bones.

Three distinctive eras can be carved out of the early human periods: The Lower, Middle, and Upper Palaeolithic. These correspond, very roughly, to the era of humans before Homo sapiens (Lower), the era of early Homo sapiens along with Neanderthals and others (Middle), and the era with Homo sapiens alone (Upper).

Evidence from the Upper Palaeolithic suggests that men hunted more: male specimens show more signs of thrower’s elbow and cranial trauma. Importantly, female specimens have these injuries, too, reminding us not to slip from more to all. But the evidence from the Upper Palaeolithic is suggestive of the pattern familiar from modern-day groups.

The thorniest debate lies in the deeper past. Ocobock and Lacy want to push the debate to the Middle and Lower Palaeolithic. This is understandable: They are most critical of ideas that different lifestyles have pushed male and female evolution apart. Indeed, their Scientific American piece wasn’t explicitly targeted at the claim that “men hunt more”. It was targeted at the claim that “men evolved to hunt and women evolved to gather” (my emphasis).

I am broadly sympathetic to this line of thinking. As they aptly point out, the long arc of human evolution is one of diminishing differences between the sexes.

This said, there is only that much evidence about the deeper past. Reduced differences between the sexes could be evidence of a host of other things. Pair bonding is the usual suspect, but as Richard Wrangham told me, self-domestication could do the job, too.

So what does the evidence say?

In the lack of much else, Ocobock and Lacy have focused on results from Neanderthals. But this only invites more questions. Why focus on Neanderthals, who are known to behave differently from us, often dramatically so? Are they an imperfect model for Homo sapiens? Or are we talking about “humans” in a more general sense? And what does the Neanderthal data even reveal? According to studies cited by Lacy and Ocobock, Neanderthals don’t show evidence for a sexual division of labor. But according to this study, they do – as much as later Homo sapiens. And it is not at all clear that differences in Homo sapiens occur only later. Quite the opposite, this study concluded that sexual division of labor gets stronger the further back in time we go. The sample was small and the interpretation is under debate. But the available evidence is hardly a death sentence for Man the Hunter — not if he allows some women to join the hunt.

Settling the matter requires a more systematic analysis of the evidence. But waiting for that, we might pause to ask if the question really matters.

4. Does it matter who brings in the meat? Yes, but not in the way you might think.

It is easy to think of sexual division of labor as evidence of patriarchy. In this vein, Woman the Hunter is bound to feel like an emancipatory companion for many. Indeed, I recently saw a play in London where a toxic-male-chairman par excellence mansplains to the only women in the board that he “men are hunters—we are risk takers”. By implication, she should know her place and stay out of men’s business.

But Starkweather wanted to question the link between hunting and equality.

It is all too easy to see sexual division of labor as being “imposed” on women by patriarchy. It can be. There are groups where women are not allowed to hunt — something that is “absolutely” a sign of unequal relationships, according to Starkweather.

But why is this the only scenario we can imagine? It suggests that women have no agency in their decisions, and that hunting is somehow superior to gathering. On the flip side of this, Starkweather posed a very interesting question to me:

“Why would women hunting be evidence of equal gender relations?”

I had always assumed that it would. But when asked, I couldn’t quite see why. Perhaps this is my own bias shining through.

This reminds me of Vivek Venkataraman’s take on the topic. Living with the Batek people in the Malaysian rainforest, he has witnessed remarkable levels of equality between the sexes. And yes, women sometimes hunt amongst the Batek. But men do the overwhelming majority of it. No problem. As he writes:

“Amongst a liberated society of equals, it matters little who brings in the meat”.

Furthermore, Starkweather pointed out that division of labor is a form of sharing. This could well indicate trust and cooperation more than power and coercion. As she told me, chimpanzee males and females do different things. But they don’t share the spoils. Humans do. In this light, a division of labor takes a different hue.

Admittedly, we should avoid putting too much politics into science. Indeed, projecting our values onto ancient humans is perhaps the mistake we should most try to avoid. But even if I get political for a moment, I don’t quite know what I would “like” to find. In this sense, the fate of Man the Hunter matters less than we might think.

The same cannot be said for the debate as a scientific issue. Sexual division of labor is often invoked in theories of human evolution. It plays a role in theories from human lifespan to pair-bonding and much more. It is one of most instinctive explanations for why gender egalitarian hunter-gatherers, like the Batek, tend to live in areas with a lot of plant foods, while many meat-dependent foragers regard baby girls as unwanted. If killed, Man the Hunter will drag many theories to his grave. Nothing wrong with that. But we should not pull the trigger without good evidence.

Conclusions

Women can be excellent hunters. The recent debate has settled this much. But men hunt much more. This pattern remains unchallenged.

The matter gets messier when we turn to human evolution. We simply don’t know what happened in the Palaeolithic, at least not in the Middle Palaeolithic and before. We’re jobs divided already between Homo erectus, as Richard Leakey suggested? Or did this pattern emerge only towards the end of the Ice Ages, as argued by Lacy and Ocobock? Unfortunately, we cannot use a time machine to find out. And the current evidence is patchy. But here if anywhere, an absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

So is “Man the Hunter” dead?

He won’t survive if he wants to monopolize the hunt. But experts knew this long before 2023. If he still deserves our attention, he does so thanks to a more casual approach. And if we give him a voice with the rebrand, Man the Hunter might well join the ranks of those who misquote Mark Twain. After all, the great author never wrote that “the reports of my death are greatly exaggerated.”

Want more of this? Subscribe to On Humans. It’s free. And I don’t spam.

This post is also free to share.

I had presented Ocobock with Frank Marlowe’s estimates on sexual division of labor of various activities in modern-day hunter-gatherers. These estimates are very orthodox and maintain that hunting is ”mostly” a male activity. Instead of disagreeing with them, she told me that:

“I honestly don't think it is an opposition to what we're saying, because again, we're not saying that only females hunted or that even females did the majority of the hunting. .. I am absolutely fine with there being a sexual division of labor. I am not fine with it being an elimination version of sexual division of labor.”

“Aha!” I thought. There is no real debate here, just a reminder for us not to slip “from moreto all”. These slips happen a lot in discussions on hunter-gatherers. (You can hear me make this slip here.) But the core scholarship remained untouched. Or so I wrote back then.

These internet trolls are not a trivial matter: Several anthropologists, all women, have told me that they receive constant abuse over email from men who cannot, in the words of New York Times, “move on” and accept that “women were hunters, too”. This makes covering the topic all the more difficult for me. I am painfully aware that my words, too, might be misused to support some paleo-fantasy of brave men and helpless women. Please, don’t do it. Nothing in this article supports such a view.

And whatever you, don’t please don’t send hate mail to scientists. It is a bizarre thing for any science lover to do.

You can also check Randy Haas for archaeological studies that suggest 50-50 gender division of big game hunting. He has additional studies out for cultures that use atlatl and sling based tech with similar findings. In regards to the UK-Great Britain argument for sampling, you could also check Megan Biesele's work; she clearly demarcates different Ju/'hoan groups based on location and language. Thanks for your investment in this topic.

I'll say that the publicity around that particular Scientific American article put my sceptical instincts in high gear. First, there's my scepticism of SI itself, which has become highly ideological over the last few years, and very partisan to the so-called social justice left, to the point where that affects their scientific judgement. ( I also found it very telling that the SI authors were critical of a simplistic "Man the Hunter" model that in its unnuanced form hasn't really been accepted in anthropology in many decades, so that seemed to be a certain amount of setting up a straw man there.) Second, I'm always wary when any popular newspaper or magazine makes claims that an entire scientific theory has been definitively overthrown - very often, it's the case that there's an active debate and the popular article is simple written by someone who's a partisan of one side of that debate, and you either get an unbalanced take, or even worse, the fact that there are competing theories or an active debate at all is simply ignored.

In the case of this article, I simply did a Google Scholar search for review papers on the topic of "sexual division of labor", and somehow unsurprisingly, the majority of them hewed to the idea that there was strong evidence of a sexual division of labor being a cultural universal and there were various theories as to why. There are also some critics who more radically reject the idea of sexual division of labor as anything innate in human cultures, but that seemed to be a minority position. (Not to say minority positions are necessarily wrong.) So this seemed to be, once again, Scientific American leading with their priors and overstating their case.