The Evolution Of Inequality Under Capitalism: A Graphic Exploration with Branko Milanović

Is capitalism an engine of inequality? I search for answers with Branko Milanović, a leading scholar of global inequality.

You can listen to the full conversation on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you find your podcasts. Just find episode 32 of the On Humans Podcast. Or you can continue reading. Enjoy!

Capitalism can cause massive economic inequalities. Indeed, a century after Adam Smith wrote the Wealth of Nations, the richest 1% owned a record-breaking 70% of England’s wealth. Not surprisingly, the later era saw the rise of a very different economic theorist: Karl Marx.

But does capitalism have to increase inequality? If so, why was the golden age of American capitalism an era of rapidly decreasing inequality? Was this “Great Levelling” a natural product of capitalist development, as theorised by Simon Kuznets? Or was it a historical anomaly resulting from the two world wars and political interventions, as argued by Thomas Piketty?

Yet more questions emerge if we take a more global outlook. Was the Great Levelling within rich countries but a veil behind which they plundered the Global South, making capitalism an inherent engine of global inequality? If so, why has global inequality reduced during the recent era of globalised capitalism?

There are very few people who can judge these questions with the same nuance and understanding as Branko Milanović. Milanović is a leading scholar on global inequality. But he is also a particularly sensitive commentator on capitalism. Born in communist Yugoslavia, Milanović has a rare ability to look at capitalism from an arms-length, without indoctrinated faith but also with a deep appreciation of the limits of its alternatives.

(By the way, Milanović writes an excellent Substack called Global Inequality and More 3.0. His most recent book is Visions of Inequality, which served as a basis for much of our conversation.)

You can listen to the full conversation on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you find your podcasts. Or you can get the gist of the story (plus a bunch of graphs) below.

I. Inequality Within Rich Capitalist Countries

Let’s start with Karl Marx.

Technically speaking, Marx was not interested in income inequality. He wrote that:

“To clamor for equal … remuneration on the basis of a wage system is the same as to clamor for freedom on the basis of the slavery system.” (quoted in Visions of Inequality, Milanović 2023: 120)

But we can probably assume that Marx was not completely indifferent to income and wealth inequalities — not while the wage-system lasts.

On this more moderate front, Marx and his followers would insist that capitalism gives much to the capitalists and little to the workers. And he was right about England of his time. As the graph below shows, the share of wealth going to the rich was increasing rapidly, climbing to 70% around the time of Marx’s death in 1883.

Source: Visions of Inequality (Milanovic 2023), Figure 4.1

This is a striking picture. But ironically, the dramatic downturn started right after Marx’s death. (Neoliberalism, globalisation, and the Thatcher-era are visible as a small uptick at the end.)

The English wealth concentration is perhaps the most intense example of the inequality during Marx’s time. So what if we change the measure? We get the same pattern but less pronounced. In the graph below, we can see the evolution of the Gini coefficient for incomes in the US and the UK.

Source: Supplementary material to Global Inequality (Milanovic 2016), Figure 2.1

On yet other measures, the US is almost back where it was. But notice that this is before taxes and social benefits. More on this below.

Source: Our World In Data

America is the anomaly, however. Fruits of the Great Levelling are very much present in many rich countries.

Source: Our World in Data

What about taxes?

Notice that these figures are before taxes and social benefits. This makes a big difference.

Despite the many tax cuts to the rich, overall taxation is doing more, not less, to reduce inequality. Naturally, higher taxes would do more. But as the graph below shows, the gap between pre-tax (market) income and post-taxes-and-transfer (disposable) income is growing in both US and Germany.

Source: Supplementary material to Global Inequality (Milanovic 2016)

In Germany, taxes are deleting almost all of the increased market inequality. In US, they are doing more than they were doing before the 80s. This took me by surprise given the infamous tax cuts during Reagan era (and after). But taxes are still progressive, and so, the more inequality grows, the more taxes bite.

A focus on taxes leads to one important possibility: that the drop in inequality during the Great Levelling was simply an outcome of government action. And this, the argument goes, was a result of Marxist parties and the Cold War, both of which put pressure on the government to go against the wishes of the capital-owning class. The drop happened despite capitalism, not because of it.

It is important to note, however, that there have been stark decreases in pre-tax inequalities, too. (As said, many of the earlier graphs were pre-tax.) And many East Asian economies don’t let taxes do almost any work. For example, Taiwan taxes very little but achieves a similar Gini score than Canada or Austria.

East Asian economies tax very little to achieve a similar Gini-scores than many high-tax Western countries. Source: Supplementary Material to Global Inequality (Milanovic 2016)

In short, taxes do a lot. But something else was driving the Great Levelling. Trade unions are one candidate. Public education is another. Organic developments in the economy are yet another. And of course, the real effect of taxes is difficult to assess, as they prevent capital accumulation and make managers less likely to negotiate large pay-rises.

So did capitalism reduce inequality during the Great Levelling? Or was this happening due to social democratic politics and other forces pushing against capitalism? We will return to this point in part III. But first, we must ask what has been happening to global inequality.

II. Global Inequality

The global story is very different. Most of the 20th Century saw global inequality increase. Some would say this is because most of the world had not caught up to the positive developments within rich economies. Others would say that the positive developments in rich economies were made possible by colonialism and what Marx called “worker aristocracy” benefitting from plunder.

Yet the story changes, again, in the 80s. Now global inequality experienced a moderate drop. (You find this on most measures, though some date the drop to the 2000s, not the 1980s.)

Global inequality went up, at least before tax, until 1980 when it started a moderate drop. Source: World Inequality Report 2022

Here are some other measures showing the same development since the 80s. The trend is clearly towards equality, especially after the turn of the Century. However, the global Gini is still above 60% – a number similar to the most unequal countries in the world.

The drop since 80’s is visible on many measures. Source: CEPR

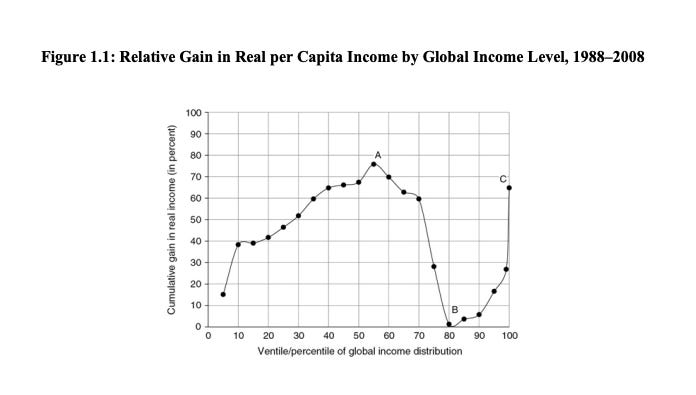

Below is a nice visualisation of where the changes are happening.

Source: Supplementary Material to Global Inequality (Milanović 2016)

As the graph above shows, the 2011 numbers have moved most in the middle. Where is this on the map? In Asia, Milanović told me. Especially China and India. You take them out and the effect is gone. But as he said to me, you cannot just exclude 3 billion people from the picture. It does, however, show that the “sunshine” story of reduced inequality is a story of Asia catching up. Africa and Latin America are not moving much or at all.

But China and India are crucial to our question. Ironically, both China and India were much more equal countries before embracing a free-market policies. But their relative equality was matched with dire poverty, and so, with an increase in global inequality.

Is this an example of capitalism genuinely reducing global inequality? Different scholars will give different answers. But one caveat must be addressed.

Global capitalism has coincided with a reduction in global inequality — but only if we measure relative inequality. There are thinkers like Jason Hickel who argue against relative measures. They ask us to look at absolutes. And here the picture looks very different. This makes sense: even a 1% increase for a millionaire is much more, in absolute terms, than a 100% increase for a poor person.

Below are two striking graphs showing the absolute wealth in the Global North vs the Global South.

Source: Jason Hickel

And here is another:

Source: Jason Hickel

This hardly looks like a convergence. It looks like a divergence.

So why have we focused on relative measures?

According to Milanović, the problem with the absolute measures is that any improvement in average incomes tends to procure inequality in absolute terms. This makes us lose sight of inequality in income distributions. In absolute measures, any improvement in average incomes is almost automatically translated to increased inequality.

Milanović gave an example of a balloon, where you draw dots. If you blow the balloon, the distances between them will grow. But this is not due to genuine changes in their relations.

This makes sense. A relatively egalitarian rich country would look, on absolute measures, more unequal than a deeply poor village where a tyrant owns almost everything. After all, the wealth gap between a poor tyrant owning 1000 dollars and a poor peasant having nothing is trivial compared to someone owning a house worth 500,000 dollars by a neighbour owning one worth 450,000. (This said, it might not be surprising that Hickel still prefers absolute measures: he is a strong advocate for degrowth. Linking growth with inequality is naturally preferable if the argument is against growth.)

Relative measures have another advantage: they give us an idea of future trends. If relative inequality is reduced, it means that the long-term trend is toward equality. This is something that graphs about absolutes fail to capture. Take the above graph with coloured “balls”. Global North has moved at a faster pace, that we can see, but we miss that parts of Global South are accelerating.

This said, Milanović agreed that we should still include absolute measures to get a more nuanced picture. (To his credit, he has been doing so for many years.) And in this nuanced picture, the rich do, in fact, receive most of the new wealth created during globalisation.

Here is a neat example of how different these can look:

Source: Supplementary Material to Global Inequality (Milanović 2016)

III. Is Capitalism An Engine For Inequality?

Capitalist countries can reduced inequality. But did the Great Levelling happen because of capitalism or despite of capitalism? For example, was public education a way to invest in “human capital” or a way for the workers to demand a better future for their children? (Two of my earlier guests disagreed on this: Oded Galor emphasised public education as a natural need for an educated workforce ; Daron Acemoglu disagreed, emphasising its roots in democratic politics and the labour movement.)

Of course, the very question depends partially on definitions. For example, is social democracy a form of capitalism? Or a political movement that fights against capitalism?

But perhaps we can say more than “it depends on definitions”. In this regard, we should compare two thinkers in particular: Thomas Piketty and Simon Kuznets.

Piketty argues that capitalism cannot, by itself, reduce inequality. For him, The Great Levelling happened despite of capitalism, not because of it. Rather, it happened because of the world wars. Wars destroyed a lot of the wealth of the rich and forced the government to tax the rich.

Indeed, wars can often serve as unintended equalisers. Milanović gave an interesting example from Taiwan: a lot of Japanese-owned assets were distributed to the people once the Japanese left after WWII. This was a great equaliser, but hardly an indigenous capitalist development.

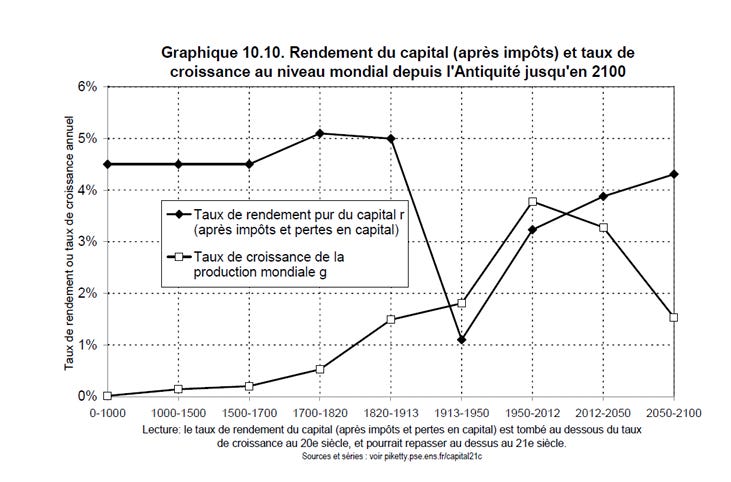

In sum, Piketty believes that inequality can be reduced in capitalist countries. But this happens due to forces that push capitalism away from its “natural course”. In the natural course, capitalism can produce gains for all. But the gains to capital owners are always above the gains to income-earners. (This is his famous r > g equation). Given that rich own more capital, this leads to ever-growing inequality. And so, Piketty argues, we need taxes, labour unions, and other counter-measures to prevent this.

The ambitious graph below captures Piketty’s thinking. Don’t worry if you don’t read French: the graph is easy to understand. It shows that capital gains (the black line) are normally above the wage gains (the white line). There is a dramatic reversal in the 20th Century. But this is likely to be a singular phenomenon, not to be repeated. Do note, however, that the lines only diverge in future estimates. (Overall, I would take such a sweeping graph with a pinch of salt...)

Source: As replicated in Milanović (2013)

Milanović has written a favourable review of Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century. But he points out some alternative ways of thinking about the problem. For example, no iron law prevents rate of profits from falling again like they did in 20th Century. Piketty assymes that they do not. But this is, as Milanović said to me, “a crucial assumption” and one which many thinkers, even Marx, would disagree with. (Marx actually thought that profits must fall as capitalism develops.)

Another thinker who would disagree with Piketty is Simon Kuznets. Kuznets was an American economist who studied the remarkable drop in inequality in post-War US. Kuznets thought that capitalist growth leads to greater inequality at first. But this is temporary. Inequality will eventually start coming down. Importantly, this would be an “organic” development within economic growth. To summarise a very complicated picture: inequality goes up when new opportunities open. Some benefit from them faster than others. But the others will catch up. And the profits made from these new opportunities start to shrink. (Unlike Piketty, Kuznets believed that the rate of profits are inclined to fall.)

Indeed, the famous “Kuznets curves” are often used as ammunition against equality-based critics of capitalism: as economy grows beyond a certain point, inequality starts to reduce in pace with growth.

I suggested to Milanovic that China could serve as an interesting model for a Kuznets-like development. He agreed. I am preparing a piece to make this more detailed. Do subscribe if you want to receive it! But the graph below is promising.

Source: Visions of Inequality (Milanovic 2023)

But wasn’t Kuznets proven wrong by the new uptick in inequality after the 80s? As the graph below shows, UK data looked good for Kuznets until 1979 — not after.

Source: Visions of Inequality (Milanovic 2023)

So was Kuznets proven wrong? Milanovic suggests that we should not be so fast. Rather, we might still want to think in terms of Kuznets waves. Kuznets was only describing one wave: that under the move from an agricultural economy to an industrial one. But since the 80s, we have been living in a new revolution of automation and globalisation. Again, some gain more than others. But again, Kuznets would hope, the early movers will lose their advantage in due time.

This is a very optimistic picture – much more than Piketty’s. (To be clear, even Kuznets did not think that this happens without some government redistribution. And he lived in an era when the top marginal tax rate hovered around 90%…)

But do we have any reason for this optimism? Yes, Milanović said. Inequality has started declining in the UK, even under the Tory government. The movement is timid, but it is there. And as I noticed after our interview, the movement is very visible in my current home town, London. Indeed, the red line below looks like a textbook Kuznets curve. (I have to note, though, that the UK’s economy is in a notoriously bad state, and this an example of “levelling down”, not "the Kuznets style “levelling up” where poverty is reduced.)

Source: X.

In the US, inequality has stopped growing after 2008 and the post-COVID developments are very promising. According to The Economist, over 30% of the US wage gap created since the ’80s has disappeared during the post-Covid era of Bidenomics. This trend is very promising: unlike the UK example, the US change is driven by increases at the bottom, not by decreases at the top.

Of course, many questions remain open. How sustainable is the downward trend in the US and UK? And is AI creating a third Kuznets wave before the second one gets to its downswing? Or is the very idea of Kuznets waves too optimistic? Is Piketty still right about the natural inclination of capitalism to produce inequality? And wouldn’t Kuznets himself need to acknowledge that taxes and labour unions were a strong force behind the Great Levelling of his time?

Global inequality presents only more questions. How should we think about the recent drop in global inequality? Is it an example of capitalism reducing inequality without any redistributive policies, simply by generating broader prosperity? Or is this a misleading story, couched in technical measures, but one behind which the rich are still exploiting the rest? And what will happen when China is rich enough to add instead of subtract from global inequality?

As Milanović warned me: “I don’t think history gives us totally unambiguous lessons”. It does not. But it can sharpen our questions.

Did you enjoy this piece? If yes, share it with a friend! And do subscribe to get more breakdowns of my conversations with historians, scientists, and philosophers. You can also listen to the conversation on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or wherever. Just find On Humans by Ilari Mäkelä.

I hope there is a better model. I find Capitalism to be exhausting, and it seems to be pretty hard on the environment....

Wealth is not a useful measure as it often just means owning shares. Essentially the problem of the poor is not low wealth, not even low income, but low consumption. And even of that, not all consumption, we need a category like "meaningfully redistributable consumption". This is not well defined yet I think. Basically you cannot meaningfully redistribute a gold watch, you can sell it and buy food but it just results in more money pursuing the same amount of food. Meaningfully redistributable consumption would be food, square meter of housing, clothing, fuel, healthcare, schooling and mass-manufactured things.

After this is somehow measured, the next thing to measure is whether there is enough of these, just badly distributed, or not enough. For example horses need a lot of farmland to feed. If the rich have a lot of horses and the poor are hungry, not good. If the rich buy old paintings, that is not an issue because not redistributable meaningfully.

Engels wrote that back that time the British working class was doing badly on these measures too, such as malnutrition. However he later retracted it.

In recent times, the developed world was doing well on these measures. However, recently home prices skyrocketed and even things like healthcare cannot cope well with immigration-related population growth. The nineties look like a golden age now.