Birth of Modern Prosperity, Part III: Daron Acemoglu on the Politics of Prosperity

This is part 3 of the Birth of Modern Prosperity. You can head here to part 1 with Oded Galor, part 2 with Brad DeLong, or part 4 with Branko Milanovic. If you’d prefer to listen to this conversation in audio, head here to Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or YouTube. Enjoy!

New gadgets are a constant feature of history — improving living standards are not. The lesson? Technological improvements do not, by themselves, lead to prosperity.

All my guests have broadly agreed on this. But they explain things differently.

Oded Galor focused on the so-called “Malthusian trap”, where better technologies often lead to denser populations, but not more prosperous populations. Brad DeLong agreed. However, he focused on the slow pace of technological progress before industrial R&D.

My third guest is Daron Acemoglu. One of the most cited economists alive, Acemoglu is best known for co-authoring the iconic Why Nations Fail. In the 2013 masterpiece, Acemoglu and James Robinson argued that powerful elites have a toxic effect on economic development. I highly recommend reading the book if you have not done so yet. But my conversation with Acemoglu was based on his new book, Power and Progress, co-authored with Simon Johnson.

For many readers, Power and Progress will feel like a very different work than Why Nations Fail. I will return to the tension below. But there is a clear continuity. Acemoglu is still looking at prosperity by focusing on politics — especially as it challenges the power of the elites. According to him, modern prosperity began when industrial technology was liberated from the iron fist of the elites.

This is Part 3 of “The Birth of Modern Prosperity”. You can listen to the episode on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your shows. Or you can keep reading for my summary and analysis.

Want to be notified about the final episode? Subscribe below. It’s free. And I don’t spam.

Acemoglu agrees with DeLong and Galor on one thing: modern prosperity is a unique phenomenon. It is not the outcome of a gradual improvement of living standards. It is an abrupt change from the past. As he told me:

“I think that there is a broad agreement on this. But the interpretations .. are different”1

For Acemoglu, the fundamental lies not in population growth but in politics.

Take medieval windmills. These were a great technological breakthrough. A peasant would have to work much less to grind the harvest into flour. Yet the peasants benefitted little, Acemoglu affirms. And contra Galor and DeLong, this wasn’t because of Malthusian dynamics. The surplus was simply captured by the elites, who used it to build cathedrals. In late-medieval France, up to 20% of output was used for church building.

According to Acemoglu, windmills and cathedrals should also guide our thinking about modern prosperity. We became rich when elites could no longer extract all the gains of modern industry. As always in Acemoglu’s writings, it is politics which explains economics.

Take the Industrial Revolution. Modern prosperity could not exist without industrial machinery. But machines did not launch a gradual ascend towards modern prosperity. As he told me:

“For about 100 years, workers did not much benefit from [the Industrial Revolution]. From around 1750 to around 1850 the real incomes of the working people in England does not seem to have increased much and their working hours increased by about 20%.”

We can support Acemoglu’s bleak outlook by examining human height. (Regular readers will know that I like to use human height as a of modern prosperity. Like any measure, it is imperfect. But it does capture something very concrete about human health and wealth — something that PPP-adjusted GDP rates never will.)

Below is a chart on the average height of British soldiers from the mid-1750s till the mid-1850s. There are ups and there are downs. But the situation is pretty similar in 1750 and 1850. This strongly echoes Acemoglu’s description.

Source: NBER

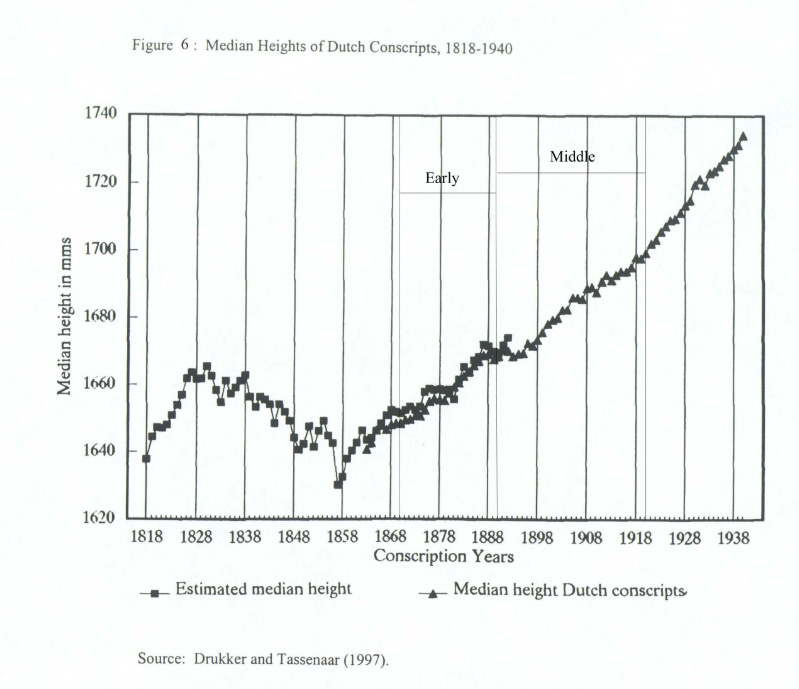

But things were about to change. Take the chart below, with Dutch data extending till the mid-20th Century.

Source: NBER

There is a dramatic turn. And the trend is very much linked to economic prosperity. Here is a telling graph from Japan, linking the growth in height with the growth in per capita GDP.

Source: NBER

In Japan — as in so many countries — economic growth in the 20th Century was coupled with increased well-being. Wealth translated to health. So why did the British living standards stagnate during the economic boom of the Industrial Revolution?

Because of extractive elites, says Acemoglu. Industrial machinery followed the logic of the medieval windmill: The fruits were picked by the rich. In some ways, things got even worse. New machines did not only fail to increase wages. They also worsened the working conditions. As he explained this to me:

“Working conditions got much worse in modern factories where there was a lot more coercion, discipline, [and a] lack of autonomy .. Children as young as five or six were working 18 hours a day in coal mines .. Infectious diseases went rampant. Pollution was unbearable.”

Importantly:

“There was no sign that any of this was automatically going to right itself.”

But it did right itself. Today’s Britain is far from a utopia. But it is a far cry from the Britain described above.

What changed?

“Britain became a democracy. With democracy, trade unions became legalized. .. And of course, without trade unions .. working people were treated extremely harshly. So that started improving. Wages started improving.”

Whether by luck or design, the direction of technology changed, too. Early machines were mainly useful in replacing expensive craftsmen with cheaper labour. The new generation of technology became more useful for workers, who gained new opportunities from perks like modern transportation. Using economic jargon, the new technologies led to an increase in the workers’ marginal productivity.

In short: modern prosperity was born when, due to struggle and luck, machines stopped benefitting the rich alone.

To support Acemoglu’s approach, I’ve added a striking graph from Branko Milanovic’s Visions of Inequality. It charts a huge increase in British inequality during the 18th and 19th Centuries, followed by a dramatic reversal in the 20th Century.

This is a powerful image, which chimes with Acemoglu’s thinking: the rich gathered the early harvest of the Industrial Revolution. Then things changed.

With this in mind, we can sketch an interim summary of Acemoglu’s thinking: Extractive elites, not Malthusian family sizes, are the historic enemy of workers and peasants. The Industrial Revolution changed little about this. The rich owned the machines, and new machines were built to suit their needs. Consequently, machines often sidelined and impoverished the workers. Modern prosperity might have been conceived during the Industrial Revolution. But to have a healthy birth, it needed political change. And this was a political change born out of conflict.

Conflict is at the centre of Acemoglu’s thinking. This is relatively rare in the profession.

“Many economists are still under appreciating .. the importance of conflict. At every turn they try to find a way of minimizing conflict. What I'm trying to emphasize [is] that conflict is key. And why is conflict key? Because choices are key. There's nothing automatic about this.“

We can better understand Acemoglu’s thinking by contrasting it to Oded Galor’s, who is a more “traditional” economist in Acemoglu’s schema. As explained in Part 1, Galor thinks that the changes were a natural outcome of the need for a more educated workforce. Acemoglu was quick to reject this thinking.

“I think any objective reading of history cannot see anything consensual about how these institutions have changed. .. Public education in Britain, for instance, came out of the democracy movement.“

Galor would simply disagree. He affirmed to me that, towards the end of the 1800s, British industrialists became pro-education. Recently, he co-authored an article looking at labour emancipation in Prussia as a natural process, where emancipating workers made sense for the industrialists.

I am not the right person to adjudicate this debate. But this seems the debate to be adjudicated. Was modern prosperity an automatic outcome of technological development, as argued by Galor? Or was it born out of a political struggle, as suggested by Acemoglu? The answer to this question shapes our thinking about our own day.

Take Galor’s position. According to his Malthusian model, only population growth has stood between technological innovation and human well-being. Technologies will continue improving—this is next to certain. And population growth has stalled or reversed in most countries. This is a happy situation: From here on, we can be confident that R&D labs will make the world better and better. (I should say: we could be confident of this if we had no external threats like climate change.)

Acemoglu does not believe that there are such guarantees. As he told me many times, “there is nothing automatic” about the positive effects of new technology. To further support his case, Acemoglu turned to modern developments. The US has obviously had no “Malthusian" population growth during the past 50 years. Yet new technologies have not benefitted a large part of the people.

As a dramatic example, men without degrees haven’t had any growth in real wages. They’ve even had some decline. And as Acemoglu told me, we shouldn’t think of this as a small minority.

“Sixty percent of the U. S. workforce does not have a college degree. On average, that group has had zero, or very small, growth in their real wages over 50 year.”

This is sobering stuff. You can see it in the graph below.

Source: Acemogu at the Oxford Union (available on YouTube)

Acemoglu’s estimates suggest that this is 1/3rd because of globalisation (read: China) and 2/3rd because of technology (read: robots).

But what can we do about this? Should we break the machines?

Acemoglu was quick to tell me that he is not a machine breaker. He believes in technology as an engine of prosperity — but only if we use it right.

“If you want an analogy: those who say block the technology are like trying to stop the flow of a river. .. What I'm saying is, let's redirect some of the flow towards places where it will do less damage and it will create more social good”

I had to smile when Acemoglu added:

“This is the On humans Podcast. So this is a really important part of the argument. .. I would summarize [my vision] as ‘a pro-human direction of technology‘. And what I mean by ‘pro-human’ is technological changes that are complimentary to humans; that increase their capabilities, .. their agency, [and] their productivity, rather than sidelining them. “

What exactly does this mean? I wish I’d asked him for more examples. I did not. But here is one which I think Acemoglu would agree with.

Robotic exoskeletons are a relatively “un-sexy” area of robotics. They draw much less attention than attempts at fully automated robots. But they should not. They are a wonderful possibility to help people, even disabled people, to perform more difficult tasks with better safety.

Photo: Exoskeleton for worker safety, as featured in Penn State Engineering

But the question remains: how do we achieve a pro-human direction of technology?

By giving more decision-making power to the workers, Acemoglu says. The logic is simple: workers would prefer machines that help them. The more workers have a voice in companies, the more companies will demand “pro-human” technologies. And the demand will shape where tech companies invest their R&D.

This is not a utopian vision. Take Germany. The industrial powerhouse is well-known for its relatively cordial relationships between unions and management. Unions sit on the board of big companies in Germany's so-called “co-determination” system. Companies also invest heavily in worker training. All of this makes companies less likely to sack as many employees as possible. The outcome? According to Acemoglu, German carmakers use more robots than Americans, but they do so without getting rid of so many employees. Rather, the robots are designed to improve worker productivity.

“I don’t want to eulogise Germany. Germany has many problems… But for the big part of the manufacturing industry, German firms [are] much better at using human skills.”

I was quite surprised by the logic. As I told Acemoglu, “I’ve never thought of unions [as creating a] virtuous circle where if you have invested in [workers] and if it's not easy to just sack them, you find ways to compliment them rather than sidelining them”.

Acemoglu nodded.

“Absolutely.”

But he added a warning about trusting all forms of organised labour:

“You are right not to have thought of it this way because if you look at the UK and the United States, unions have often not played that role because union/management -relationship has been conflictual enough that the more cooperative role has not emerged.”

Despite this warning, I left the conversation with a bolstered faith in social democracy. This came as a small surprise, as Acemoglu is often described as a “centrist”. (The label is mentioned twice on his Wikipedia page.)

So is the lesson that even centrists should lobby for labour unions? Or has Acemoglu leapt to the left? I pressed Acemoglu on this by asking him to compare Power and Progress to the more whiggish Why Nations Fail. He chuckled and responded:

“We all evolve, don’t we!”

On a more serious note, he explained that Why Nations Fail is still relevant for understanding why certain countries are richer and more powerful than others. However, Power and Progress explains how to translate being rich and powerful into shared prosperity. Here is my summary in the bluntest of terms: Why Nations Fail was about national income — Power and Progress about median income.

Nevertheless, I cannot imagine that Power and Progress will gather as broad-based praise as Why Nations Fail. Critics will undoubtedly point to the litany of issues with, for example, labour unions. These critics are bound to gravitate more towards Galor and DeLong in the explanation of modern prosperity. (You can head here for Brad DeLong’s take on the book, in a conversation with Noah Smith).

My personal concern revolves around the idea of “pro-human” technology. I like the idea. But where to draw the line? Were tractors a “pro-human” technology, increasing the agency of a lonely farmer? Or were they an “anti-human” technology which sidelined a massive amount of farm workers? In hindsight, I think that the tractor has played a hugely positive role in history. But how could we, or labour unions, have known this beforehand? To give a more timely example: How should we think about AI translators? For my work, DeepL is a hugely positive development, allowing me to work more efficiently in Chinese. But professional translators complain about a slump in jobs. In the modern economy, it seems that almost any technology will empower some workers while sidelining others.

These worries aside, Acemoglu does offer us a timely lesson from history. Modern prosperity was not born alone. It was born together with modern politics. There was nothing automatic about it. To succeed in the economy of modernity, we need a politics of shared prosperity.

This was Part 3 in the series on the Birth of Modern Prosperity. You can listen to the episode on Spotify or Apple Podcast. To be notified of the final part with Branko Milanovic, make sure to subscribe to the On Humans newsletter. It is all free. And trust me, I don’t spam. (I should probably write more, not less…)

All quotations have been simplified by deleting filler words, filler phrases, and other parts not critical to the argument. Given the sheer number of such edits, I have decided to hide them to ensure legibility.