Origins of Humankind, Part II: An Unusual Ape

The story continues! In part II, we zoom into the first half of the hominin story, trying to find the deepest roots of our human oddities.

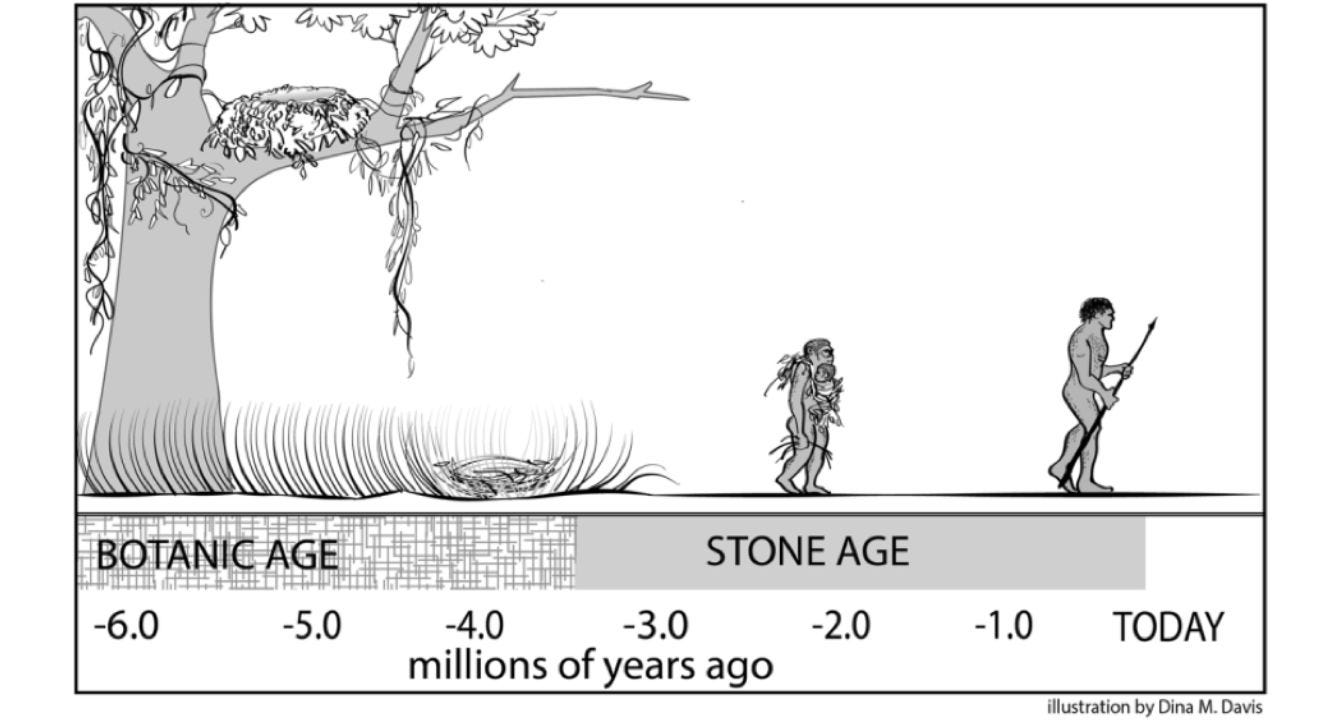

The Stone Age gets all the glory. But what about the all-important period before the first flint tools? To get humanity going, our ancestors had to wander through millions of years of what anthropologist Dean Falk calls the Botanic Age. It's a misty epoch shrouded in mystery, yet it may hold the key to humanity’s most defining traits, from dance and music to our peculiarly large brains.

Guiding us through this shadowy stretch of prehistory is Dean Falk herself — Distinguished Professor of Anthropology and one of the world’s foremost experts on human brain evolution.

You can now listen to the episode wherever you get your shows, or you can keep reading for highlights.

Listen

Listen: Spotify | Apple Podcasts | Other Players

Watch: YouTube

This is part of the Origins of Humankind series produced with CARTA (UC San Diego). You can enjoy each episode as a stand-alone, or head here for the whole experience.

Highlights

Prefer reading to listening? Not a problem. Here’s a summary of our conversation in three parts.

1. The Misty Epoch

Humans and chimpanzees split around 6 million years ago, give or take a million. The first stone tools appeared a bit over 3 million years ago. What happened in between? This first half of hominid evolution is clouded in mystery. But Dean Falk thinks it set the stage for much of what would come. And in early 2025, she coined a name for it in a book of the same name: Botanic Age.

Why the “Botanic Age?” Because our ancestors almost certainly made tools from plant materials. After all, even chimpanzees do this. And we don’t have to go to extreme examples, such as the female chimpanzees in Senegal who craft wooden spears to hunt bush babies. All great apes practice botanical crafts. They do so daily. Why? Because they sleep in trees. But for great apes — big in size — this is a risky business that requires a supportive “bed” or “sleeping nest” to avoid falling. Indeed, every chimpanzee, gorilla and orangutan alive starts their bedtime routine by weaving an elaborate basket from branches. No monkey does this. All great apes do it. Most likely, so did our ancestors around 6 million years ago.

This activity is all-around the ape world. It happens every night.

But human ancestors left the trees. They did so gradually. But as they did, they adopted an upright posture.1 This had cascading effects.

As Darwin observed, our ancestors freed their hands for more extensive tool use. But equally important, Falk argues, they lost their nimble feet. Indeed, the chimpanzee feet look like an extra pair of hands. They can be used to grab things and manipulate things. The more our ancestors spent time on the ground, the more their feet shaped for walking — not grabbing. In Falk’s words, “Our feet became weight-bearing instruments.”

2. Speech, Song, and Child Support

Babies were the first to notice the new foot design. It got increasingly difficult to cling to the mother for support — something all other primate babies do. This might have triggered one of the greatest revolutions in the human story.

Falk believes that mothers probably carried their babies in baby slings — a portable version of the “ape-like-tree-nests” they were used to making anyway. But even with this caveat in mind, babies had to be put down sometimes. And babies don’t exactly like this. They cry. And mothers try to soothe them with vocalisations. Falk’s famous “putting-the-baby-down hypothesis” suggests that language’s roots may lie in an unlikely cradle: the soothing murmurs of mothers who, no longer able to let infants cling, traded touch for vocal comfort. This is not to say that our early ancestors were speaking. But Falk thinks this began the long march towards modern human language.

Like all theories about this early epoch, this one is speculative. But I was happy to support Falk’s speculation with one remark: Babies learn language, not adults. Therefore, any theory of the origins of language must explain why language fitted into the early development of the human infant well before they hunted, gossiped, mated, or did any of the myriad of things that language proved useful for. Falk’s theory does this with ease.

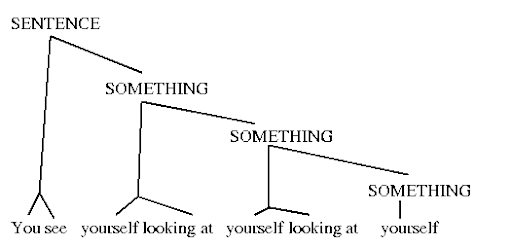

On the other hand, her theory does meet a formidable foe: the school of linguistics who, in the footsteps of Noam Chomsky, focus on the capacity of all human languages to create infinite arrays of meanings from a finite set of signs. In technical terms, such scholars try to explain how humans evolved brains capable of grasping recursive grammar — the ability to embed one thought inside another, like the nested clause in the sentence “The dog that scratched the cat went to sleep.”

Soothing baby talk seems to have little power to explain this Holy Grail of Chomskyan linguistics.

Falk responded by taking me through the baby’s journey from womb to grammar. It takes around two years. Grammar might be the end-point. But much needs to happen before it. And “baby talk” between parents and infants is a big part of this path. The same goes, she said, for the origins of language.

“You can learn a lot about the evolution by looking at the development.”

All this said, the origins of language will hardly be solved by just one theory. Language contains multitudes. As Falk noted, standing upright might have also contributed to language via another path.

Rhythm.

Human speech swings—it leans on rhythm like a drummer on a beat. No other primate matches our cadence: neither the hoots of chimps nor the howls of gibbons. And this capacity has leaked beyond the boundaries of language. Humans are dancers and drummers with an exceptional capacity to keep the beat. Why? We don’t know. But it might well have to with upright walking. Once our ancestors started walking more upright, their fetuses became exposed to the steady beat of the bipedal walk. Chimpanzee-style walking does not produce a clear beat for fetuses to hear (and feel) in the womb. Human walking does. And the persistent rhythm of these ancient footsteps might have paved the way towards our propensity — unique amongst primates — towards drumming, singing, and dancing.

3. Towards the Human Brain

We should be wary of the cliché that bipedalism merely liberated our dexterous hands. Walking trapped our feet more than anything else. But Darwin wasn’t entirely wrong. Hands were freed — and he believed this kicked off a virtuous cycle: freed hands led to tool use, which led to bigger brains, which led to even better tools.

For decades, this idea fell out of fashion. Fossils showed that bipedalism came millions of years before stone tools and larger brains. But I asked Falk: might Darwin have been more right than we’ve assumed?

My hunch was based on two observations.

First, the tools. Stone tools arrive late — but as Falk often reminded me, our ancestors almost certainly used tools long before that, made from botanical materials. That soft technology has vanished, but the behaviors may stretch as far back as bipedal walking.

Second, the brains. Australopithecines indeed had (roughly) chimp-sized brains. But in 2000, Falk demonstrated that some of them already had more human-like brain organization. Size isn’t everything.2 Wiring matters.

By pushing back the start of extensive tool use and human-like brain organization, we might be making Darwin’s theory plausible again. Is Darwin back in the game? Falk nodded approvingly.

“Absolutely! It makes perfect sense.”

(Off the record, she warned me many times of taking pure brain size as the only measure that matters in brain evolution. For example, she did a famous analysis of Homo floresiensis — the famous “Hobbit” of Flores Island — and found that, again, its chimpanzee-sized brain was hiding a remarkably human-like organisation.)

All this suggests that brain evolution might have been more gradual than we have come to believe. Yes, brain size starts a rapid increase quite suddenly with the rise of Homo erectus and such. But the brain might have been re-organising much before. Beyond square footage, it might have been the new floor plan that welcomed the dawn of humanity. And as Falk said, by the time you see the re-organisation in the broken skull, internal rewiring must have been going on for a long time.

This is not to say that brain size doesn’t matter. “It clearly does”, Falk said. So leaving the Botanic Age behind, we can ask: Why did our more recent ancestors start growing their brains? Floor plans aside, why was the real estate growing so fast?

Falk believes language was key in driving the need for a bigger brain. But need alone isn’t the whole story. We also have to ask: How could the body afford such a metabolically expensive organ? Most theories focus on energy. Brains burn calories — a lot of them. So how did our ancestors feed this growing appetite? By cooking meat? Digging for marrow? Cracking open shellfish? Perhaps even fermenting foods by accident? No one quite knows.

But Falk has added another crucial piece to the puzzle — not about energy, but about heat.

A brain can overheat. A big brain overheats easily. According to Falk’s “radiator theory”, human ancestors lucked out. Standing upright had changed the way blood circulated to the cranium. As luck would have it, in one lineage of Australopithecins, this new “plumbing” happened to be well suited for cooling a big brain. Indeed, the “radiator theory” implies that chimpanzees could never have grown a big brain, even if they’d “wanted” one. Their heads would have overheated.

As before, it looks like the seeds of our human oddities were sown already in the mysterious aeons of the Botanic Age.

But seeds have to mature. And mature they did! The Stone Age began. And the first proper “humans” soon walked on Earth. Next week, we will walk through this all-important chapter with the iconic Chris Stringer.

As Jeremy DeSilva and others have pointed out, this did not mean they started from all fours and slowly rose up. They might well have started from a gibbon-like posture, where they move in trees upright. Whatever the starting point, we do know one thing: the more time our ancestors spent on the ground, the more their skeletons started resembling the basic human plan.

Even there, the “debunking” of Darwin might be a bit too enthusiastic. As I discussed with Jeremy DeSilva, Australopithecines’ brains are sometimes 20% larger than those of chimpanzees. This is hardly trivial. Furthermore, they are not “obligate bipedals” like later human species. Obligate bipedalism comes later and is associated with a more dramatic increase in brain size. In other words, some bipedalism leads to brain growth, and obligate bipedalism leads to much more brain growth. Again, the pattern is not quite as opposed to Darwin as we might think at first glance.

I’ve long been convinced that the 70,000 year old artwork consisting of crosshatched lines represents a string figure. The making of cat’s cradles is an algorithmic process, analogous to Chompskian grammar.

https://www.oldest.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Blombos-Cave.jpg