The story of China is not just the story of one nation. It is the story of a large chunk of humanity — at times a quarter of our species. And for better or worse, it is the story that is now shaping the century ahead.

To cover this fascinating topic, I recently published a three-part mini-series on Chinese history. This was based on hours of conversations I had with MIT Professor Yasheng Huang and ChinaTalk’s Jordan Schneider. Our conversations were based on Huang’s masterwork, Rise and Fall of the EAST — the first book I would recommend to someone trying to understand the origins of today’s China.

Doing this series was a hugely rewarding exercise. I do recommend it to anyone interested in the subject. But I wanted to offer something for those who don’t have three hours to spend on Chinese history — not to speak of the hours needed to read the 400+ page book. So here is my attempt at dissecting the main lessons from those sources into a more accessible package.

In Part 1, I dissect Huang’s insights into imperial China and its long legacy in modern China. Part 2 discusses the origins of China’s recent rise. Part 3 discusses China’s present condition. This is not a book review, but an attempt at making the book’s ideas more accessible.

If not otherwise stated, the quotations are either from our conversations or Rise and Fall of the EAST.

I think that’s enough of a primer. Let’s go!

1. Imperial China

Around the year 500, China resembled Renaissance Europe. There were many power bases and competing ideologies. Huang calls this period of disunity China’s “European moment.” Curiously, it was also the most technologically inventive period in Chinese history.

For example, the graph below tracks the index of Chinese inventions per capita: the CDI-score compiled by Huang’s team. The CDI-score peaks during China’s “European moment” (“The Han-Sui Interregnum”, see the third grey bar). And it corelates with the presence of Buddhism and Daoism. Huang’s explanation is straightforward: high levels of Buddhism and Daoism indicate high levels of intellectual diversity.

This one graph is the key to Huang’s central argument: political and cultural centralisation stifles innovation. As he writes:

"Too much autocratic stability is detrimental. This conclusion is not based on Western values and ideology, but on China’s own history."

This diagnosis will be central to Huang’s analysis of Chian today. But staying on ancient times, Huang also shows that the CDI score negatively correlates with the sheer size of a centralised “Chinese state”. Again, the more politically fragmented the Chinese landmass was, the more inventions it produced.

The moment of political and intellectual fragmentation was not only a period of technological inventions. Chinese intellectuals were busy writing — and they did so in a surprising style As Huang writes:

“Individuality, rather than collective morality, animated intellectuals of this age. Writers and artists searched for “naturalness” and “spontaneity,” and abhorred politics and public morality.”

For example:

“[One of the poets of this era, Ruan Ji] cried when his neighbor .. died, but he wined and dined when his own mother passed away. In response to a rebuke, he replied: ‘Surely you do not mean to suggest that the rules of propriety apply to me?’”

This is as far from stereotypically “classical” Chinese culture as you get. And this is very much in line with calling this era China’s “European moment”.

But the moment ended. It ended with the founding of the Sui Dynasty in 581. Critically, the Sui found a magic recipe to homogenise Chinese society and do it in a way that served the emperor and eroded competing ideologies. This recipie was the keju civil service exam.

China’s famous civil service exams were used for centuries to select government officials—those famous “mandarins.” The keju system had genuinely meritocratic and democratic elements. The state supported broad-based primary education centuries before the European states had anything to say about the matter. As Huang writes:

“Imperial China built and funded a large-scale educational infrastructure in order to overcome the advantages of wealth and incumbency. .. These preparatory schools provided government stipends and tuition waivers. .. The Keju preparatory system was massive in scale. The early Ming imperial bureaucracy operated 1,435 administrative units and 1,318 dynasty schools—almost one school per administrative unit.”

Indeed, Huang’s own studies concluded that wealth was not a major predictor of success in the exams. Social mobility was a real thing. This made China escape the grip of a European-style aristocracy.

However, the civil service exams also sucked Chinese intellectual efforts into serving a pro-state status quo. No independent intelligentsia developed — something that made China different from Europe, Russia, and so on. The Galileos and Voltaires of China were given a deal: they got political power. In exchange, they had to accept the existing order.

In short, the civil service exams served as the deep current of Chinese imperial history. On the bright side, they made China a country where education was the path to success. Political power was won with the power of the pen — not with the power of the sword (or the surname). On the darker side, the exams bolstered a homogenous culture with the emperor at the top. China was a “frictionless autocracy” where the emperor faced little competition from aristocrats, little criticism from the intellectuals, and no challenge from religious leaders.

2. Communism and China’s Rise

Things changed — thrice. First, the keju civil service exams were banished in 1905. Then, the imperial system crumbled in 1911. Finally, Mao Zedong’s communists swept into power in 1949. But the legacies of the keju system lingered on. At points, Mao turned viciously against them. At other times, he embraced them. And yet others, they simmered as the silent conditions for China’s economic takeoff.

Most obviously, Mao inherited a highly autocratic and centralised political culture. However, he turned against China’s long-venerated role of bureaucracy and formal education. The Cultural Revolution was the epitome of this curious mix. Schools were closed. Mao’s critics were purged. The rage of the youth was turned against the state itself.1

This much is well known. But Huang points out a less well-known way in which the legacy of the keju system influenced communist China: China had a high level of so-called “human capital.” For example, China had strikingly high literacy and life expectancy rates. In addition, China had a homogenised culture, a common language, and a shared cultural code.

Huang’s TED Talk is excellent in this regard. It focuses on a comparison between China and India. To quote some of his most striking statistics, China’s female literacy in the ‘90s was 68%. That’s double India’s 34%. This is wild. But it gets wilder:

“In China, the definition of literacy is the ability to read and write 1,500 Chinese characters. In India, the .. operating definition of literary is the ability … to write your name in whatever language you happen to speak.”

To boot, Chinese culture was significantly more homogenous than India’s—another legacy of the civil service exam. (It is no coincidence that the English word for the Chinese “common language” 普通話 is “Mandarin,” after the civil servants selected by those very exams.)

High literacy was fuel in China’s economic tank. Cultural homogeneity could have been a blessing or a curse, but it certainly was a blessing when China started mass-producing products for foreign markets. Overall, these factors — all legacies of the civil service exams — were pushing China past many of its low-income peers, such as India. And they pushed with force: even during Mao’s catastrophic policies, China’s GDP growth outpaced India by an average of 2.2%.2 Once Mao’s policies disappeared, China was ready for a proper take-off.

We should note the hidden lesson here: According to Huang’s analysis, China’s rise was heavily built on the government stepping aside and letting China’s natural strengths play their role. Unsurprisingly, the government sees things differently. They might do so at their own peril, as we will discuss soon. But first, let’s turn to the post-Mao years.

According to Huang, the 1980s were a golden era for the Chinese economy. Incomes grew fast in both urban and rural areas, supported by grass-roots entrepreneurship and financial liberalisation in rural banking. The countryside was the focus of much of this action. As he explained in our chat:

“We're even talking about land reforms. We're talking about village elections. We're talking about rural financial liberalization.”

Huang was visibly annoyed that this part of China’s miracle is still ignored by economists who, like his earlier self, only focused on the 90s and 00s when foreign investors made China into the factory of the world.

“We are talking about large scale financial institutions developing extremely fast in rural area in the 1980s, and the Western scholarship knows nothing about that period. There's no curiosity about that period. “It's not that important!” [people say]. But hey, that affected 800 million people! And then the overwhelming narrative is ‘oh, China can grow without financialization’. Every time I think about this I feel so frustrated and really sad.”

To sum up, China’s growth story was built on two underappreciated causes: the legacy of the civil service system, which paved the way for China’s high literacy and cultural homogeneity, and second, the surprisingly liberal policies that transformed China’s countryside in the 1980s. These pillars are often ignored by both Western observers and the Chinese state-sponsored pundits who focus, unsurprisingly, on the roles of foreign investors and the government itself. This becomes central to Huang’s analysis of China today.

But first, let’s look at how the 80s met its end.

3. The China We Know Today

The Tiananmen Square massacre ended the golden era. Liberal reformers like Zhao Ziyang allied with the protesters and were sidelined. (Despite being the Chairman of the Party, Zhao was ousted and placed under house arrest.)

The Post-Tiananmen leaders, like Jiang Zemin, opted for a model of state capitalism based on luring foreign investors. Huang calls this the “Shanghai model” after Jiang’s city of origin. (Huang is from Beijing, so this is a dire insult…)

The Shanghai model contributed to China’s skyrocketing levels of corruption and now-infamous urban-rural gap. Instead of supporting rural entrepreneurship, the new economic model started relying on migrant workers moving to factories built with foreign money. This produced one of the world’s largest mass movements of humans—and the Chinese economy that we know today. But the rural areas stagnated.3

Besides a shift in economic thinking, Tiananmen Square led the way to a change in China’s political culture. To counter the ideological roots of the protests, the new leaders emphasised patriotic education. They succeeded. As anyone familiar with the matter can testify, younger generations of Chinese today are often ultra-nationalistic. I highly recommend Zheng Wang's Never Forget National Humiliation on this topic.

This is the soil from which Xi Jinping’s reign grew. After all, he is a nationalist leader who has promised to fight corruption and urban poverty while cleaning China from the environmental problems unleashed by the quest for pure economic growth. And he is delivering. His ultra-nationalistic policies are infamous. His anti-corruption campaign has prosecuted over 2 million officials.

On the brighter side, China is a leader in green technologies. And China’s green turn is not just about making money by churning out solar panels and EVs. No foreign media covers Beijing’s pollution anymore. And back in 2019, I conducted field research on a 10-year fishing ban on the Yangtze River. This is not a policy one would have thought possible in China in the early 00s.

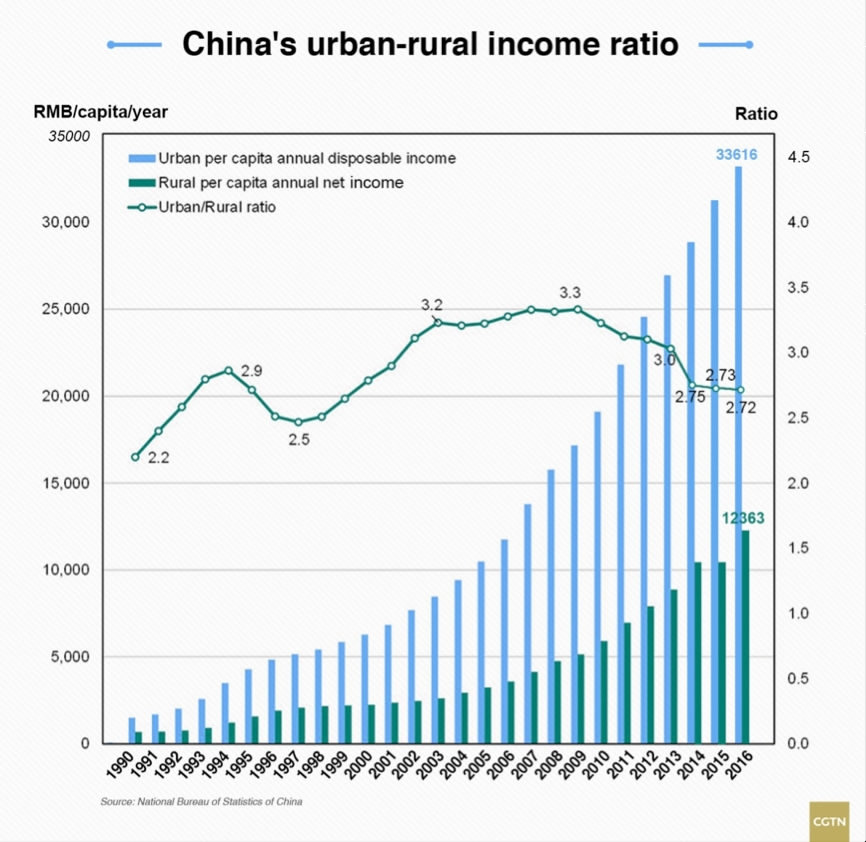

The urban-rural gap is also shrinking in China. You can see this in the official data below (follow the green line, which curves down after Xi took office in 2008).

If you don’t trust official Chinese data, trust Branko Milanovic. A legendary figure in inequality research, Milanovic has no particular sympathies for the Chinese Communist Party. But he confirms these basic patterns: China’s rural growth is so substantial, he told me, that he can detect it in the datasets on global inequality.4

In sum: Huang sees the 80s as a golden era. It ended abruptly in 1989. Dead were not only the bodies of many protesters. Dead was also the policy of grassroots liberalisation. And in the stench of this death, China took a turn towards hugely unequal economic growth, high corruption, and increased environmental problems. Xi Jinping is a natural counter-reaction to these developments.

So, did China need Xi Jinping? I asked him.

“I buy into the objectives: environmental improvement, clean government, improving the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution. I just don't buy the methods.”

As Huang put it, the fundamental question is:

“Does doing all of that require that you get rid of the term limit? Does it require this degree of centralization? They are fighting corruption and it has been 11 years — 11 years! Maybe [they could] rethink this particular way of tackling corruption. I would argue transparency, disclosure of the government, more media scrutiny, more legislative scrutiny can help in terms of tackling corruption, rather than this kind of a purge approach.”

Indeed, Xi Jinping’s autocratic methods have reversed many of the pillars of China’s success during the reform era. This might be catastrophic for the fate of the Chinese people — even setting aside the existing suffering of dissidents, Uyghurs, and so on.

Indeed, the increasingly authoritarian policies erode many of the hidden freedoms and protections Chinese entrepreneurs have benefitted from. This brings us back to where we started from: China’s high inventiveness during its period of disunity—it’s “European moment”.

According to Huang, China has always been most innovative when autocratic leadership hasn’t stifled it. The decades after Mao brought another such moment. Yes, China was autocratic. But China has been much more liberal than the government wants to acknowledge. Even after Tiananmen, Chinese entrepreneurs and academics have benefitted from countless freedoms now under threat. They often operated from the safety of Hong Kong and Taiwan. They were often trained in foreign universities. They often worked with foreign investors and academic collaborations. Oddly, these hidden layers of diversity are not only neglected by Chinese leaders but also by Western academics. As Huang said during our chat:

“ I am constantly struck by the fact that Xi Jinping and so many Western observers agree with each other perfectly. They all believe that it was the infrastructure; it was the power of the government. They see eye to eye with each other!”

What they miss, Huang argues, is the hidden conditions for China’s rise now under threat. With China’s economy slowing down, Huang’s warnings are as timely as ever.

And here is another warning: Xi Jinping’s decision to abolish old succession rules has created a ticking time bomb of political chaos. What will happen when Xi eventually steps down—or dies? Nothing pretty, Huang thinks.

On the other hand, China still has many good fundamentals, especially in human capital. Here, the legacy of the civil service exams is still wind in China’s sails.

Will China’s entrepreneurs find a way to thrive in the new environment? Or has the government invited an end to the long era of economic optimism? Head here to hear more. You will find links to our conversations, Huang’s works, and many more resources on Chinese history.

So what do you think? Does Huang help us understand China today? What does he get right? What does he ignore? Do share your reactions in the comments!

Thank you for reading this piece! If you enjoyed it, you might also want to check out my mini-series on the Birth of Modern Prosperity. Guests include Daron Acemoglu, Branko Milanovic, and Brad DeLong.

This article is also open-access, so feel free to share it with anyone!

That’s it for today! My next longer piece will discuss the origins of war and peace. Expect juicy insights into hunter-gatherers, pacifist cave paintings, and warring chimpanzees. If you want a primer, find On Humans episode 48 wherever you get your shows, or check my short videos on the topic on YouTube. Enjoy!

Contrary to some simplistic suggestions, the Cultural Revolution was not an authoritarian system turning against society. In many ways, it was an attack on the state by Mao and his young followers. Just see the many conflicts between Red Guards and the military — or what happened to the leader of the state, i.e. the president of China.

I get this number from Huang’s TED Talk.

As Scott Rozell’s remarkable research shows, rural children are now paying the price: whilst Shanghai tops international rankings in school performance, many of China’s rural students struggle with vitamin deficiencies, stomach worms, and uncorrected myopia.