Why Agriculture?

Our ancestors lived from hunting and gathering. Suddenly, humans around the world abandoned this way of life. Why?

Agriculture changed everything. Within a few thousand years, most of our ancestors moved from wandering in the wilderness to farming in villages. Today, over a third of the Earth’s landmass has been claimed by farmers.1

Traditionally, this “Neolithic Revolution” was celebrated for opening the gates of civilisation. Recently, it has been compared to the original sin. But whatever our take on agriculture, we should be puzzled by one thing: why did our ancestors start to farm in the first place?

I. The Puzzle

Originally, I used to think of farming as a kind of technological breakthrough —not unlike the Industrial Revolution of more recent times. In this model, planting the seed was like harnessing the steam. We might never know why these methods were invented. But once invented, they spread far and wide. They did so because they benefitted their users, whether Neolithic agriculturalists or early British capitalists. But this theory has two flaws.

First, there was no one “Neolithic Revolution”. There were many.

Tellingly, the term “Neolithic Revolution” was coined by the Marxist archaeologist, V. Gordon Childe. He was understandably impressed by the idea of a single world-changing revolution. But Childe was very focused on the Middle East. Today we know that humans transitioned to farming several times around the world. And they did so within a remarkably short time span (archaeologically speaking). This raises a puzzle: Why would this novel idea emerge now, and only now, in several places with no contact with each other?

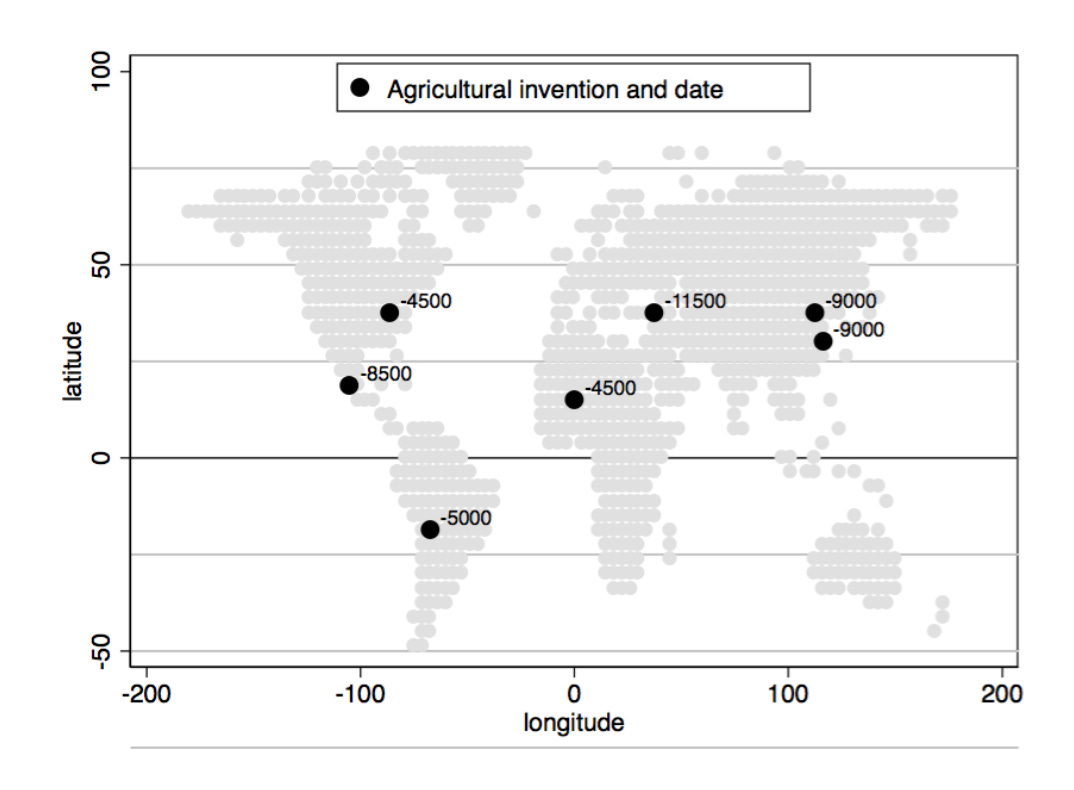

Figure 1: Agriculture was developed independently in at least seven locations around the world. The above picture is from Matranga (2022), citing original data from a 2009 article by Purugganan & Fuller. The true number of locations is probably higher than this. For example, it is becoming increasingly clear that agriculture was independently developed in Papua New Guinea.

The mystery thickens when we notice that farming was no blessing for the farmers. Steam engines made a lot of sense for the British capitalists. However, it is very unclear what early farmers gained from their “invention”. They had worse teeth than their ancestors. They had more joint problems. They probably worked harder. And they were literally shorter. Jared Diamond might have exaggerated, but he was not hallucinating when he called agriculture “the worst mistake in the history of the human race”.2

So why did early farmers decide to settle down? And why would their neighbours adopt it, too?

We might finally have an answer. And the answer is linked to climate change.

Enjoying this? Keep reading. But do also subscribe to On Humans! You’ll learn something about humans in the future, too.

Linking agriculture to climate change is not a new idea — not as such. This vague link has long formed my pet theory on the matter. After all, the dawn of agriculture coincides with the end Pleistocene’s “Ice Ages” and the start of the Holocene’s warm weathers. Ice Age was no time to sow the seed.

But this theory has a simple flaw: there was never an “Ice Age” in the tropics. If the Middle East was warm enough 10,000 years ago, Sudan was warm enough 20,000 years ago. And anyway, the end of the Ice Age doesn’t explain why humans started working harder for worse health. Or so argues Andrea Matranga, the author of a remarkable paper on the topic.3

This article is based on my conversation with Andrea Matranga. You can listen to our conversation on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your shows. Or you can read more below.

II. The Theory

Matranga’s answer is remarkably simple: humans did not start farming because of a rise in temperature. They started farming because of a rise in seasonality. Summers became warmer, winters colder. And so, old ways had to give way to new.

This rise in seasonality was caused by so-called “Milankovic cycles”, bizarre fluctuations relating to Jupiter’s gravity. During the dawn of agriculture, these cycles combined to cause a large contrast between summer and winter — especially in the northern hemisphere. As Matranga outlines in his paper:

“Sunlight seasonality in the northern hemisphere was higher [during the dawn of agriculture] than it had been at any time since our species had acquired behavioral modernity, some 50,000 years prior.”

This caused problems for nomadic hunter-gatherers.

“In the northern temperate zone .. hunter-gatherers could gorge themselves during the hot rainy summers, but they risked starving in the harsh winters.“

You might guess the relevance to agriculture in Middle East, China, and the like. But agriculture was also invented in Africa and Peru. They did not experience harsh winters. But their pre-monsoon draughts became worse.

“[Close to] the equator, vast areas would come to life during the wet season, only to become barren during the dry one.“

How could hunter-gatherers survive strong seasons? By storing food for the winter, Matranga suggests. But with storage comes settlements. And with settlements, the path to farming was ready.

Indeed, it might be a mistake to focus on farming as such. Farming was the outcome of a process that started long before. Nomadic hunter-gatherers cannot simply “invent” agriculture. They need to settle down first. Then, farming can take place.

The Natufians, early dwellers of the Levant, are a classic exemplar. These people were technically hunter-gatherers — they lived on wild foods — but they had bread on their menu. They harvested wild barley and ground it to flour. The gain was stored for the winter. But storage required becoming sedentary. With the years, their actions started having an impact on grains. Slowly, one generation at a time, the grains grew bigger and the stalks thicker. The grains became “domesticated”. The people became “farmers”.4

Importantly, the Natuffians suffered from bad health before agriculture. They were shorter than their ancestors. They had made a trade-off. They ate worse foods to avoid the risk of starving in the winter. And remarkably, we know that this worked out. Evidence from bone growth shows that nomadic hunter-gatherers had it worse on one measure of health: their bones show more evidence of so-called “Harris lines”. These lines — like tree rings — are evidence of short famines, typically during winter, followed by growth spurts in the spring. Nomadic hunter-gatherers had more food overall. But they experienced more famines than their settled neighbours. Winters are hard when living without storage.5

III. The Data

This is not just a nice theory on paper. It is also possible to test. After all, seasonality was not an equal problem everywhere. Just as London today has milder seasons than New York, so some areas in the early Holocene experienced milder seasons than others. Europe was one such example. Curiously, Matranga notes that Greece and Italy had average temperatures similar to the Fertile Crescent. But they had less seasonality. The result? No invention of agriculture in Europe. The same holds for all the temperate regions of the southern hemisphere, from South Africa to Argentina and Australia.

Matranga tested this idea with a mathematical model. The model is fed with ancient climate data. Munching through these numbers, the model spits out predictions about where agriculture would be likely to start. In the original version of the article, Matranga also uses a contagion model to show that farming spreads faster to neighbours who experience high seasonality. Neighbours with milder seasons were more resistant to farming. (These results were not included in the final version due to space concerns.)

Is this geographical determinism? Not quite. There are plenty of areas with increased seasonality and no agriculture. It is not that seasonality created agriculture. Humans did. But seasonality led some groups to search for certain answers. And this made agriculture more likely.

IV. The Big Picture

Matranga is not alone in linking agriculture to climate change. But he is one of the first to think about this climate change as a change in seasonality. And he is the only person to test whether this predicts the dawn of agriculture around the world, not just the Middle East. If the results stand the test of time, we might have solved the puzzle once and for all.

Questions remain, of course. Eventually, agriculture spread to areas of low seasonality — even Britain. Why? Also, agriculture did not disappear when seasonality diminished. Quite the opposite, farming grew more intense. Why?

In our conversation, we discuss these later developments. We talk about the role of migration and state coercion in the later development of agriculture. We wonder if ancient states were led by Machiavellian tyrants or irrigation experts. We note a much-neglected downside to the hunter-gatherer lifestyle. And as always, we finish with my guest’s reflections on humanity.

You can listen to our conversation on Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your shows. Just search for On Humans and episode 42. Or head directly to Spotify below.

If you want to dig deeper into the data, you can get the original full-length version of Matranga’s paper for free here.

And finally, if you like this material, do subscribe to On Humans below. It is free. And I don’t spam.

If you count “arable land”, the figure is close to 50%. For this and many impressive graphs, see Our World in Data’s page on Land Use

Diamond’s article is free to read here. He gets a lot of the data from Paleopathology of the Origins of Agriculture, edited by Cohen and Armelagos (1984).

Matranga (2022) gives an excellent literature review of the more recent evidence.

The peer-reviewed version was published by The Quarterly Journal of Economics. I highly recommend reading the earlier “working paper” version, as it includes more data that was cut due to space concerns. You can read it for free.

Alice Roberts explains this dynamic well in Chapter 2 of Tamed. For example, she lays out a possible scenario of settled harvesting of wild cereals that could lead to domestication. Below is an excerpt of how this could work for one of the traits of domesticated cereals: a stronger spine or “rachis”:

“In fact, it’s possible that selection for a tough rachis started to operate even before farming began. Imagine being a hunter-gatherer, bringing back armfuls of wild cereals to your settlement to process them. You’ll drop plenty of seeds on the way. But if any of the wheat you’ve gathered has a tough rachis mutation – those ears will stay intact. When you get back and start threshing, it’s inevitable some of those grains will escape, germinate and grow. Did the first fields spring up around the threshing floors, before any sort of cultivation was practised? It’s certainly a possibility…”

See Matranga (2022) for sources, especially page 38.